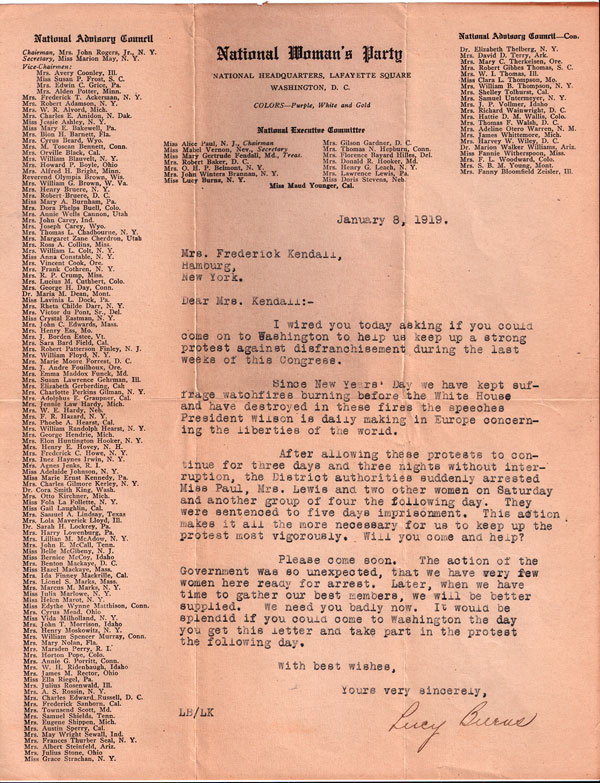

In January, 1919, Ada Davenport Kendall had joined a band of distinguished women from all over the United States to march on Washington and protest in support of women’s right to vote. They chained themselves to the fence outside the White House, so that they couldn’t be driven away, and they were taunted and beaten…

Earlier this spring I was contacted by a woman named Melissa Harshman who, along with several others, have formed the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial Association, a group dedicated to honoring the lives of the suffragists and establishing a memorial in their honor at Occoquan Park where my great-grandmother, Ada Davenport Kendall, and many others suffered terribly for the right to free speech. Last month, several women reenacted the Silent Sentinel protest in front of The White House to commemorate passage of the 19th amendment, giving women the right to vote. They wore period clothing and carried replicas of the purple, gold, and white banners the original women held. Their purpose: to keep history alive.

Many of the women protesting with my great-grandmother in 1919 were society women, wives of prominent politicians, elegant and dignified, and they couldn’t believe how they were treated when all they were asking for – peacefully – was the right to vote.

Many of them were jailed. Ada was sent to the notorious Occoquan workhouse – where conditions were far more ghastly than most people know. The Occoquan, she wrote, was “a place of chicanery, sinister horror, brutality and dread” from which “no one could come out without just resentment against any government which could maintain such an institution.” Family legend has it that her husband, Frederick Kendall, printed her letters to him in his newspaper and eventually word of the atrocities to these women spread around the country. She got the jail, the jailers, and some dreadful politicians into so much trouble that she was released early, and theybegged her to leave the jail.

Of course, she refused. She insisted that every single suffragette who was still being held – without charges, without a trial, and treated with great cruelty – had to be released as well. After that she was confined to solitary again and when she protested that treatment again by going on a hunger strike she was forcibly fed – which, the way it was done back then, was another form of torture.

Eventually, the idiots in Washington realized that they were making idiots of themselves. Husbands slowly began visiting their wives and couldn’t believe the condition they were in. The 200 or so imprisoned women were eventually released and Congress passed the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, which gave women the right to vote. (Still, twelve states rejected the amendment and women still weren’t allowed to vote in 1952!)

These are some of the stories my mother and others have told me about my great-grandmother, Ada Davenport Kendall:

A man was beating his horse with a whip in front of her house, and she dashed outside, grabbed the whip, and began whipping him with it.

She had a beloved parrot who she called Pol.

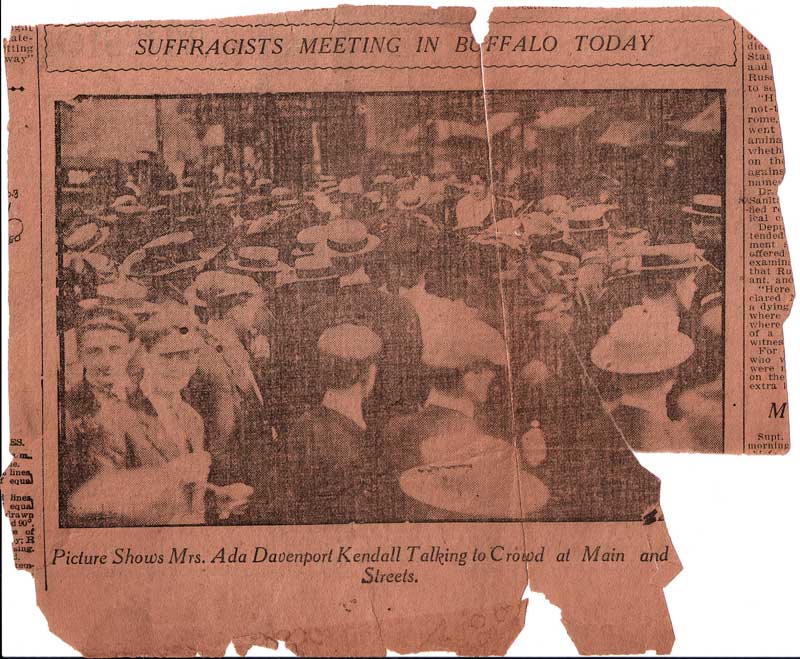

When she was twenty, she became the first woman reporter for the Buffalo Express. The then city editor, Frederick Kendall, (he later became publisher) objected strenuously – but within two years they were married. I love to imagine their conversations!

My cousin Peter was seven when he went to Bam’s – as we always called her – for Christmas in the mid-1940’s. He writes: “The whole family was there. At night I slept in the bedroom above the kitchen. There were grates that allowed the warm air from the first floor to rise. I’m awake in anticipation of Christmas morning. Suddenly I hear a door open to the kitchen from the outside. I look through the grate and see a shabby man enter and go to the icebox (refrigerator), get something, and leave. A while later it happened again with a like person. This went on all night long. In the morning it was Christmas. But all I wanted to know was what that was all about. Sam [our uncle] told me that Bam always left the door open and the fridge stocked, so the homeless (the word, then, of course, was “bums”) could have a meal, and the Christmas one was always special. I had never heard of anyone doing such a thing, and I never have since.”

Another story we great-grandchildren were told was that she wanted a fireplace in one of the rooms in the house. Her husband said no, and when he came home there was an axe in the wall. When he inquired about it she replied, “That’s where I want the fireplace.”

While Ada was incarcerated at the infamous Occoquan workhouse, she spent much of her time in solitary confinement, where she made friends with one of the many rats, shared with it her meager portion of maggot-infested food, and named it Machiavelli.

The Poet

After asking relatives for stories they remembered about her, and researching her biography, I came across this mysterious poem she wrote that made me feel closer to her than ever:

THE LADY OF MY DREAMS

Like flash of wild bird in the night,

A tender fleeting thing, —

Or like a breath of soft sweet air

When Winter kisses Spring, —

As falling rose leaves in the rain

Her fragrant presence seems ;

She is the answer to my soul —

The lady of my dreams.

With wild unrest she fills my heart,

The tender fleeting thing,

And yet I would not touch her hand

Or still her wandering.

As well imprison opal fire

Or catch the moon’s white beams ; —

And so I follow with my soul

The lady of my dreams.

Ada Davenport Kendall