Imagine this: It’s evening and Mr and Mrs Smith wait for their friends, the Martins. The two couples stodgily tell meaningless stories, banter nonsense, speak staccato truisms, and offer irrelevant quotes and poems. They’re joined by the Smiths’ maid, Mary, and her lover, the local fire chief. (Since there’s no fire, they leave.) The absurdity is hilarious. The Martins puzzle over is their relationship with each other–eventually they realize they’re husband and wife. The couples continue to argue, but so nonsensically that it’s increasingly comical. Tempers flare. Communication breaks down. The play ends with the same dialog it opened with, but this time it’s spoken by the Martins instead of the Smiths. And even that is funny, although it’s hard to know why.

That is the basic plot of The Bald Soprano, an absurdist play by Eugène Ionesco. When I was a senior in high school, I played the part of Mrs Smith. During rehearsals we laughed our way through every scene. Sometimes we would fall into laughing jags that had us gasping for air. Our director had to teach us tricks to keep from laughing (like “don’t look at each other” and “pretend you’re alone on stage”–which sometimes made us laugh harder). We also learned comedic timing: how to be aware of the audience’s shouts of laughter and to pause in our dialog so our next lines could be heard.

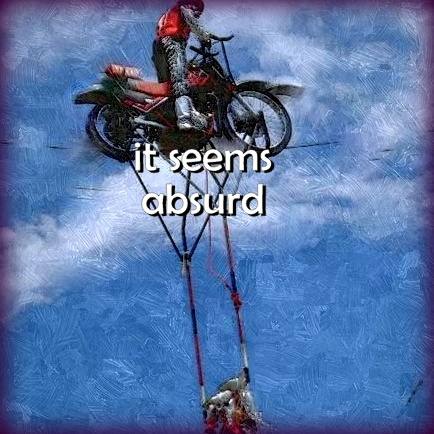

Where we are today feels like a scene from an absurdist play. It’s utterly nonsensical to imagine a terrifying world ruled by fear of contagion, sickness, and death. It’s preposterous that a tiny bug has created lockdown and forced isolation. How absurd that we are only safe isolating ourselves from everyone else—the very opposite of our human nature, which is social. Maybe we can’t rewrite the current script, but maybe we can enjoy it more as though we’re in an absurdist play. Maybe we can interpret it differently—as a wake up, for example, rather than as terror. We can examine our relationships and make sure they’re intentional, meaningful. We can look into our own hearts to come to an intuitive knowing of what to do and how to do it. Through the absurd situation we find ourselves in, we can come to understand what really matters. Absurdism grew out of the dreary, post-World War 2 existentialist movement, which pointed out pointlessness, meaninglessness, and nothingness. The absurdist perspective also brings to our consciousness mystery and hilarity.